Can I learn Chinese if I'm tone deaf?

Yes, you can!

First of all, if by “tone deaf”, you mean that you are embarrassingly out of pitch when you sing, I have great news for you — you absolutely CAN learn Chinese!

You only need to make a brief visit to a karaoke bar in Shanghai or Beijing to know that there are tons of people in China who can’t sing very well. Yet these people have no problem whatsoever with hearing or speaking the Chinese language.

In fact, your genetic talent (or lack thereof) for music has absolutely no bearing at all on what your ability of Chinese could be.

The truth of the matter is: Despite all the hoopla about the challenges of mastering a tonal language like Chinese, Chinese tones are actually way simpler than musical tones!

Chinese tones are easier than musical tones

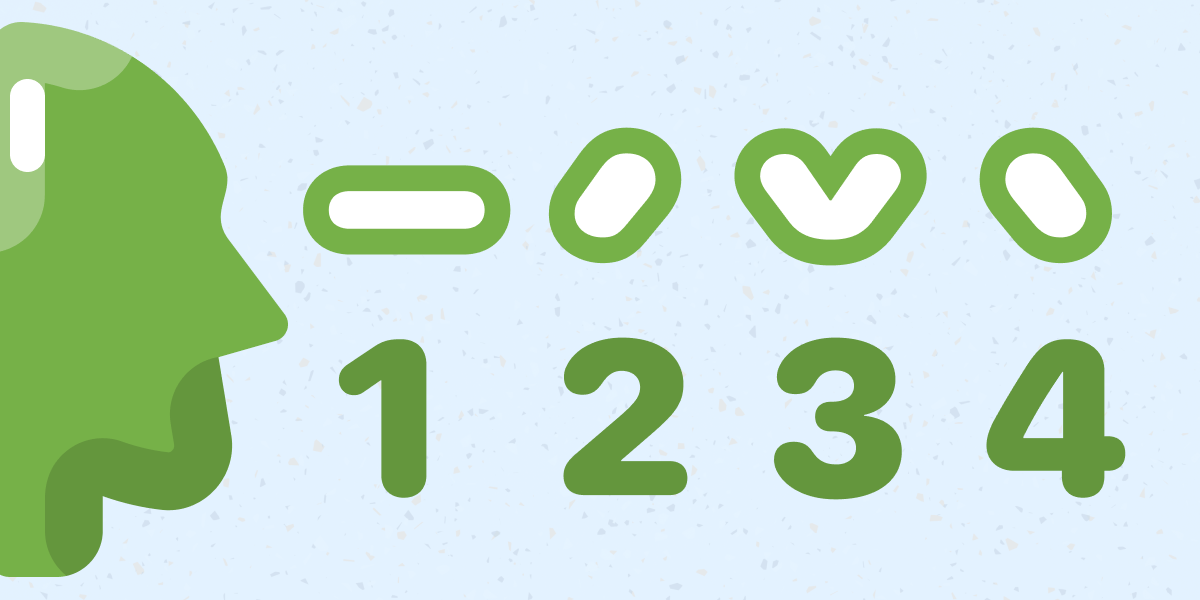

In music, there are a variety of difficult concepts to grasp, such as half tones, whole tones, octaves, harmony and scales. In contrast, Chinese only has 4 tones (as well as a relatively uncommon fifth neutral tone).

Every single Chinese word has one of those 4 tones, and these tones are indicated by tone markers that look like little lines above the romanized form of the word.

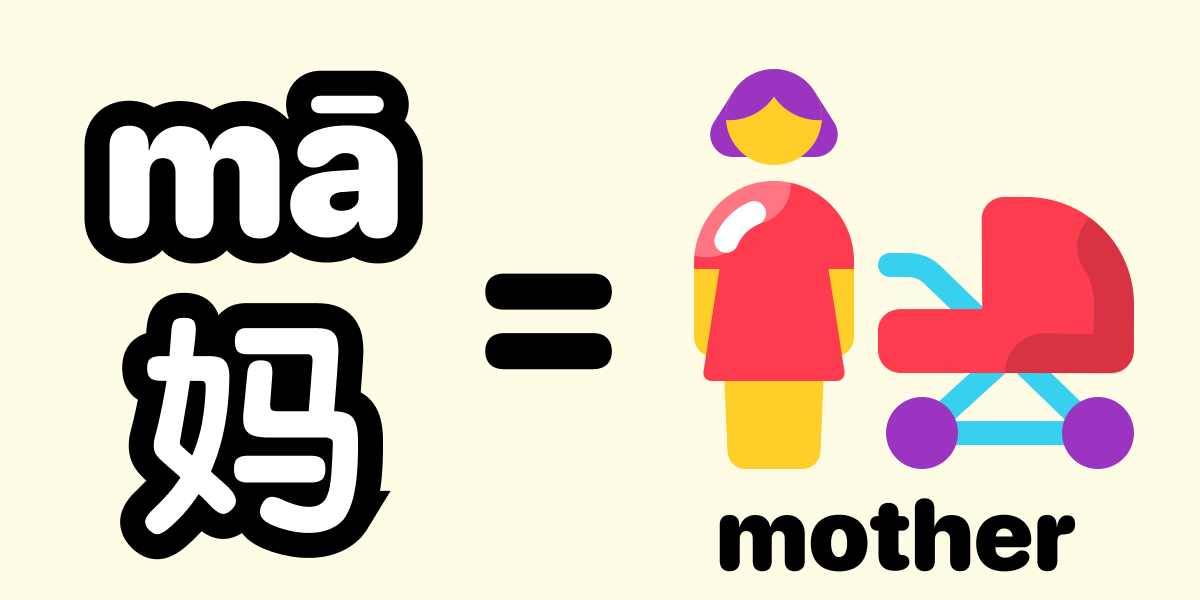

For example, the word mā means mother. Notice that there’s a little line (¯) above the a. That means that this word is pronounced with the first tone.

Chinese pronunciation is remarkably straightforward

Chinese sounds unfamiliar and even sing-songy to the untrained ear.

“Ching chong ding dong” — this is an old, racist saying referring to how Chinese sounds. It’s rarely used today, because it’s offensive, but the truth of the matter is, to many non-Chinese speakers, the Chinese language sounds just like a cacophony of random screeches and clangs.

But once you start seriously learning Chinese pronounciation with the right method, you’ll realize this isn’t true at all!

Each word consists of a syllable, coupled with a tone. For example, the word 中 “zhōng” which means “middle”, as in “middle seat” or “middle country (China)”, has the syllable “zhong” paired with the first tone.

To be able to say this word, you just need to know how to pronounce the syallable “zhong”, and then use the correct tone to say it.

It’s a very logical process that can be learned, practiced and mastered.

There are no exceptions or gotcha’s

When you come across a new word in Chinese, you just have to take a look at its romanized form (we call this romanized form pinyin) to immediately know how to pronounce it.

In the earlier example we used, the character 中 is the word, and zhōng is its pinyin form. Once you’ve learned how to pronounce the syllable “zhong” and how to vary your pitch to produce the first tone, you’ll instantly be able to say the word “zhōng” flawlessly.

It’s a very regular, straightforward process.

Contrast that to English — which is known for quirky pronunciation rules.

For example, “caret”, “carrot” and “karat” are all spelled differently in English, but pronounced the same way!

And the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw is famously said to have joked that the word ‘fish’ could legitimately be spelled ‘ghoti,’ by using the ‘gh’ sound from ‘enough,’ the ‘o’ sound from ‘women’ and the ‘ti’ sound from ‘action.’

This will NEVER be the case in Chinese. If a word has a different pinyin from a different word, it is always pronounced differently!

English also contains tones!

If you think that tones are a problem that is unique to Chinese, think again!

In actual fact, tones are used frequently in every language — including English. The difference is that tones are used to convey emotions, not to differentiate completely different words.

For example: imagine yourself saying the word “No” to a naughty and misbehaving child. You’re probably saying “no” in an angry tone. Your pitch starts off high, and ends low, because you want to give your “no” a resounding, stern emphasis.

Congratulations — you’ve just used a falling tone, which is the fourth tone in Chinese!

Another scenario: imagine yourself nodding along to a friend as they explain something. You use the conversation filler “uh-huh” to prod your friend to continue speaking. Say “uh-huh” out loud and pay attention to how the tone changes from “uh” to “huh” — it’s a falling tone at first, and then a rising tone.

Congratulations again! You’ve now used a falling-rising tone, which is the third tone in Chinese!

You’ve been subconsciously using tones in your speech for years.

Chinese takes it one step further. It’s the same set of tones, just used in a more intentional way.

And once you figure it out, there are no exceptions or gotcha’s to be aware of.

It just takes a bit of practice, but soon you’ll be able to confidently say anything in Chinese.

The best ways to learn Chinese tones

I’ve written an extensive guide on ways to learn Chinese tones. Check it out at the links below.

Kai Loh

Kai Loh